One of the prominent ironies of electrification is that products designed to be more environmentally friendly currently have relatively unsustainable supply chains. Electric vehicle (EV) battery manufacturing is particularly fraught with ESG challenges. For example, two million tonnes of water are required to make just one tonne of lithium—enough for around 100 EVs—with extraction techniques often proving deleterious to the areas affected.

Digital battery passports are one idea for improving these important components’ green credentials. From February 2027, all vehicles sold in the EU must include a QR code with information such as its material contents and embedded carbon footprint. Over time, OEMs will also need to demonstrate adherence to pre-set metal recovery rates and recycled content specifications.

As this data shapes consumers’ purchase decisions and pressures global automakers to improve their sustainability, the mission to decarbonise EV batteries will inevitably involve a re-evaluation of the entire value chain. From critical mineral processing to cathode manufacturing, every step must be reconsidered. But is there a common problem throughout?

Recognising the potential

In 2020, two graduates from University of California, Berkeley—Lukas Hackl and Bilen Akuzum—set off on a trip to visit companies throughout California’s and Nevada’s upstream EV battery supply chains. “We visited mining operations, battery recycling facilities, cathode active material producers, and more,” Akuzum tells Automotive World. “We kept our ears open to where the problems were really coming from.” To their surprise, regardless of a supplier’s place in the value chain, the same waste product was cited repeatedly.

Sodium sulphate is a by-product resulting from the use of sulfuric acid and caustic soda during the refinement of critical metals for manufacturing common cathodes, including nickel-manganese-cobalt. It is also created during battery recycling—the Argonne National Lab’s EverBatt model estimates that 800kg is produced per 1,000kg of battery materials processed. Sodium sulphate does have limited commercial use, but the uptick in EV battery production means that responsibly disposing of greater quantities becomes difficult.

The potential for cleaner electrified chemical processing, Hackl adds, has “massive” potential. “There are many different ways to approach this in automotive—from green hydrogen to carbon capture—but we wanted to pick the area that addressed the actual problems of suppliers today.” As such, in 2021, Hackl and Akuzum co-founded Aepnus Technology—as Chief Executive and Chief Technology Officer, respectively—to reduce emissions in battery supply chain chemicals through ultra-efficient electrolysis.

Closing the loop

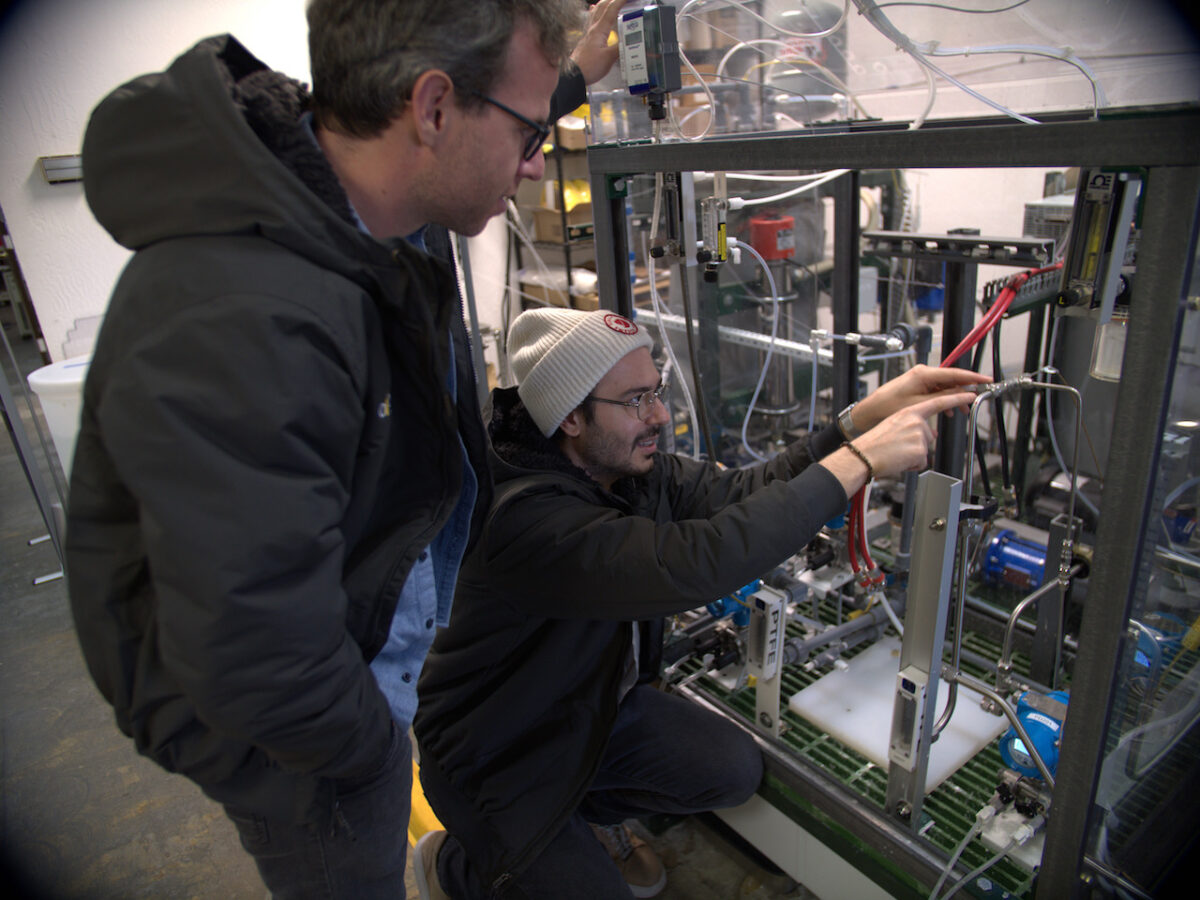

Aepnus Technology’s solution was to develop a new electrolyser—a stack of metal electrodes separated by membranes and fed aqueous feedstocks, which are then turned into desired chemical products through the application of electricity. “This is how we can take sodium sulphate and transform it back into the two chemical reagent workhorses of the battery industry: sulfuric acid and caustic soda,” explains Hackl. Essentially, the company takes what was formerly a waste product bound for landfill and reintroduces its constituent parts to the supply chain.

The chemicals produced through this method, he continues, are equally as viable as primary-sourced equivalents. “Traditionally, these molecules are delivered by truck or train in overly concentrated form, which must then be diluted at destination for actual use.” Instead of keeping quantities of water for this purpose, customers will be able to keep Aepnus Technology’s electrolyser on site. Importantly, this means they can mitigate logistics costs and produce cheaper—depending on the price of electricity—battery processing chemicals in the exact concentrations required.

“This can speed up battery time-to-market in many ways,” says Hackl. “Because there’s no longer a waste stream, companies don’t need a permit for its mitigation; the loop is closed.” Aepnus Technology commissioned its pilot scale system at the start of 2024, with an unspecified customer already on board. Akuzum states that initial output will be small—two tons per year, a drop in the ocean when a single battery plant produces “tens of thousands of tons” of sodium sulphate. “Much like battery R&D itself, a lot of time and money will go into the early commercial demonstration of the technology. Afterwards, scaling isn’t that much of a challenge.”

The missing piece of the puzzle

In its 2021 National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries, the US Department of Energy highlighted the vulnerability of domestic supply chains to overdependence on foreign imports, which is also a prevalent concern in Europe. Aepnus Technology’s electrolyser raises the prospect of onshoring and improving the sustainability of important battery material processing chemicals. At the time of writing, Akuzum states the company is 10% of the way to its final target. In June 2024, the company secured US$8m in seed funding led by Clean Energy Ventures, which it hopes will lead to significant progress on a commercially-viable reactor within the next two years.

This is the missing piece of the puzzle for the clean energy transition

“Electrochemistry holds the key to decarbonising an industry that is otherwise very difficult to improve,” emphasises Hackl. Combined with the increasing global investment in renewable power generation, he anticipates a future where cheaper and greener electricity combines with EV production at every level to form a virtuous loop that eliminates waste. “Sulfuric acid and caustic soda are some of the most widely consumed industrial chemicals in the world. There’s a sea of customers, and by establishing partnerships with manufacturers early, we hope to incorporate our electrolyser in their new, EV-ready facilities.”

Although he cannot name specific companies, Akuzum states that OEMs and several players in the battery value chain are already engaging with Aepnus Technology at this early stage. “No one wants to talk about how much waste is involved with EV battery production, but we want to show that there is a solution,” he concludes. “The market pull we’re experiencing demonstrates that this is the missing piece of the puzzle for the clean energy transition.”