3D printing has been around for almost three decades but OEMs have only recently begun to realise its commercial benefits beyond prototyping. It has significantly altered the ways OEMs approach model designing, development, and manufacturing. It is helping car manufacturers across the globe shorten their product development phase, reduce prototype costs, and test new ways of improving efficiency.

With 3D printing, OEMs are able to use CAD software to design parts and then print a prototype themselves, saving them both time and money.

Previously, OEMs outsourced the process of prototyping to machine shops, which not only resulted in additional costs but also took weeks to produce a part. Moreover, if the produced part needed modification (which in most cases it did), then the modified blueprint was sent to the machine shop again for production, resulting in a repeat of the entire process.

Due to lower costs and turnaround time, this technology has given OEMs the flexibility to use a fleet of printers to try out multiple designs at once, rather than being limited to one design and then restarting with another in case the first result did not meet expectations. This has largely helped OEMs boost quality levels as they do not waste too much time applying modifications to their designs and then testing them.

Who is using 3D – and what for?

GM uses 3D printing technologies of various kinds, such as selective laser sintering (SLS) and stereolithography (SLA), across its design, engineering, and manufacturing processes and rapid prototypes for about 20,000 parts. Chrysler uses 3D printing for prototyping a wide variety of side-view mirror designs and then selecting the one that looks and performs the best. Ford, on the other hand, has been one of the earliest adopters of 3D printing technology. It runs five 3D prototyping centres, of which three are in the US and two are in Europe. The company churns out about 20,000 prototyped parts per annum from just one of these centres (Michigan, USA).

Other OEMs, such as Mitsubishi – which bought its first 3D printer in 2013 – have been late adopters of the technology.

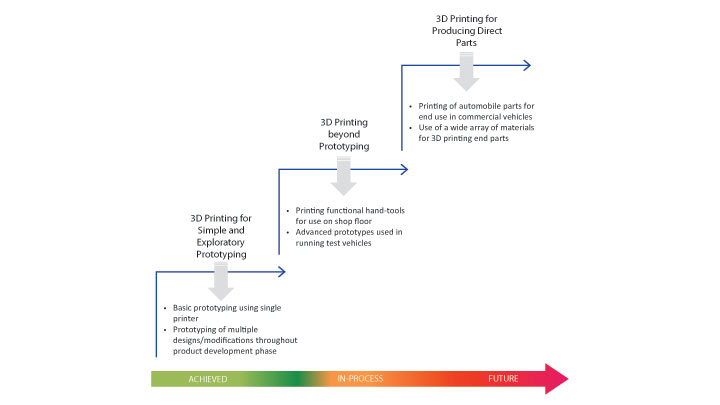

While 3D printers continue to be widely used for rapid prototyping across the industry, several large vehicle manufacturers have advanced into the next stages of 3D printing technology adoption. Although still in nascent or experimental stage, these OEMs have applied 3D printing to produce hand tools, fixtures and jigs to enhance production efficiency at floor level. Ford, which is one of the most advanced users of 3D printing, uses this technology to produce calibration tools.

Leaders in the use of 3D printing, such as Ford, also apply the technology to prototype parts that are of such strength that they are installed on running test vehicles. The company uses engine parts, such as intake manifolds, from 3D printing white silica powder, to install it in its running test vehicles. With the use of 3D printed prototypes of components such as cylinder heads and intake cylinders in test vehicles, Ford is successful in avoiding the requirement of investment castings and tooling, and in turn saving significant amount of time and dollars.

Another advancement in 3D printing encompasses the use of new and innovative materials. While most companies use silica powder, resin, and sand, few OEMs are innovating with forming test parts out of clear plastics. This allows them to validate designs as the team can visualise what is happening inside the part. Chrysler uses transparent plastic in 3D prototyping their differential and transfer cases. By inserting oil, they can monitor whether the gear stays well-lubricated under the prototyped design/model.

The use of metal as a printing material is an innovation that, although still in its nascent stage, is being used by OEMs such as BMW to 3D print (using SLM technology) a metal water wheel pump for its DTM racing car. Auto-parts manufacturer, Johnsons Controls Automotive Seating, also uses 3D printers to print metal parts that have complex shapes and are difficult to produce using traditional welding.

With these new applications taking the industry by storm, several OEMs are increasingly investing in and exploring the uses of additive manufacturing. While few companies have been slow in adopting to 3D manufacturing initially, it is expected that they will soon come up to speed with the advances in the use of this technology, given the holistic benefits it offers.

Strati is born in 44 Hours…

Strati is born in 44 Hours…

Arizona-based Local Motors has created the world’s first 3D printed car, Strati, which it plans to launch in 2016 (providing it passes the crash and other requisite tests).

Strati’s body and chassis are completely 3D printed; components such as wheels and suspension, however, are sourced from Renault. The battery-operated car is expected to cost in the range of US$18,000-30,000 and have a top speed of 50mph (80kph).

…Shuya to follow!

Taking a cue from Local Motors, Chinese OEM Sanya Si Hai has unveiled its own 3D printed vehicle called Shuya. While Shuya takes relatively longer (5 days) to print and has a top speed of only 25mph, it costs only US$1,770.

The biggest challenge: seeing beyond the prototypes

One of the biggest drawbacks of 3D printing is that in an industry driven by volumes, its current speed cannot match the production volume requirements, thus inhibiting the use of this technology for direct part manufacturing. This in a large way restricts the use of 3D printing for mass production. While there is ongoing research into high-speed additive manufacturing, it still remains a concept.

Even if large automobile components are to be produced using this technology, they still need to be attached together through welding or other techniques. This lowers the benefits accrued from 3D printing the parts in the first place. This aspect of 3D printing is also being researched, and unlike high-speed additive manufacturing, 3D printing companies have made good ground in building large 3D printers that do not restrict the size of the component produced.

Another indirect but real challenge to the widespread adoption of additive manufacturing is high levels of intellectual property theft. Since additive manufacturing products can only be patented (and not copyrighted), there is much ambiguity regarding what falls under patent protection. Until there are clear guidelines regarding intellectual property and 3D printing, OEMs will remain wary regarding the extent to which they should use this technology.

The biggest challenge, however, is the mindset of OEMs which continue to look at 3D printing as primarily a prototyping tool.

On reflection

The automotive industry must take its cue from the aerospace and defence industry, which, along with additive manufacturing companies, has heavily invested in developing new materials and technology in 3D printing to meet evolving requirements. Instead of sitting and waiting for 3D printer manufacturers to bring about new uses of 3D printing for the automotive industry, OEMs themselves should proactively seek to innovate with the technology.

Companies such as Ford and BMW, which are exploring other uses of this versatile technology have the opportunity to not only save costs, but also improve overall performance. And this is what may just provide these OEMs the competitive edge they are looking for. The question is, who else is willing the take the big leap of faith?

Case study: BMW and Stratasys

BMW uses 3D printing’s FDM technology to build hand-tools for vehicle assembly and testing. In addition to the financial advantages, FDM process helps the company to make ergonomically designed assembly tools that perform better than traditionally made tools.

BMW uses 3D printing’s FDM technology to build hand-tools for vehicle assembly and testing. In addition to the financial advantages, FDM process helps the company to make ergonomically designed assembly tools that perform better than traditionally made tools.

For one such tool, BMW worked with 3D printing company, Stratasys, to reduce the weight of the device by about 72%, thereby enhancing its ease of use considerably. Apart from improving the handling abilities of tools, the technology has helped enhance functionality. The company has managed to print parts with complex shapes that allow workers to reach difficult areas specific to BMW-produced vehicles. In one such instance, the company created a tool using 3D printing for attaching bumper supports, which features a convoluted tube that bends around obstructions and places fixturing magnets exactly where needed.